MultiVariate (Dynamic) Generalized Additive Models

The mvgam 📦 fits Bayesian Dynamic Generalized Additive

Models (DGAMs) that can include highly flexible nonlinear predictor

effects, latent variables and multivariate time series models. The

package does this by relying on functionalities from the impressive

brms and

mgcv packages. Parameters are estimated

using the probabilistic programming language Stan, giving users access

to the most advanced Bayesian inference algorithms available. This

allows mvgam to fit a very wide range of models,

including:

You can install the stable package version from CRAN

using: install.packages('mvgam'), or install the latest

development version using:

devtools::install_github("nicholasjclark/mvgam"). You will

also need a working version of Stan installed (along with

either rstan and/or cmdstanr). Please refer to

installation links for Stan with rstan

here, or for Stan with

cmdstandr

here.

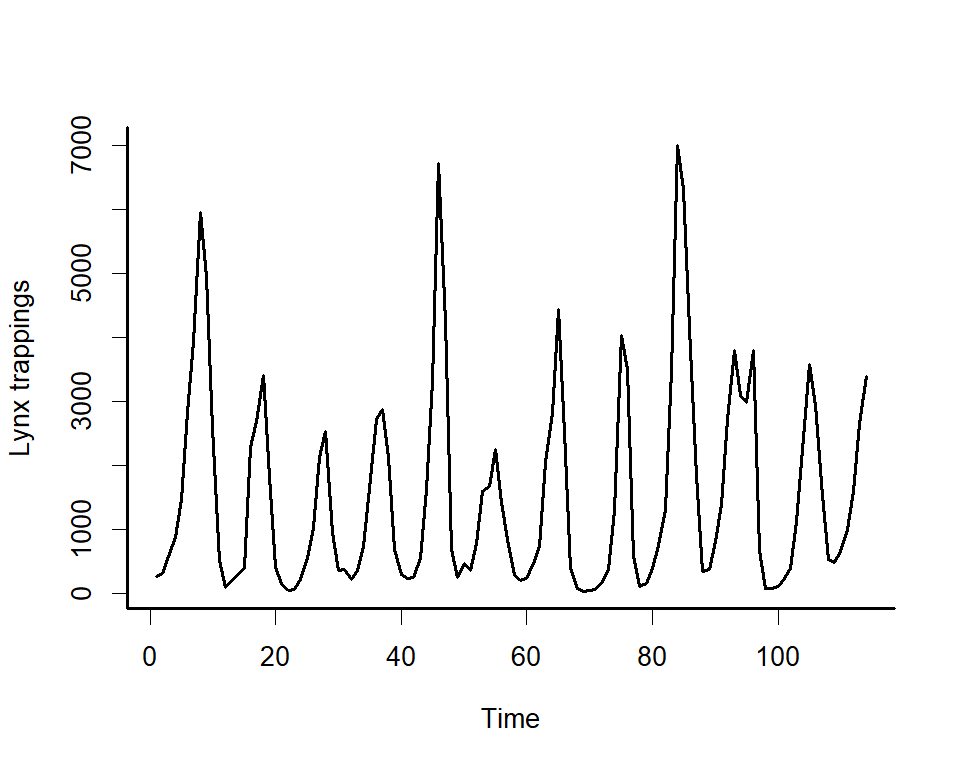

We can explore the package’s primary functions using one of it’s

built-in datasets. Use plot_mvgam_series() to inspect

features for time series from

the Portal

Project, which represent counts of baited captures for four desert

rodent species over time (see ?portal_data for more details

about the dataset).

data(portal_data)

plot_mvgam_series(

data = portal_data,

y = 'captures',

series = 'all'

)

plot_mvgam_series(

data = portal_data,

y = 'captures',

series = 1

)

plot_mvgam_series(

data = portal_data,

y = 'captures',

series = 4

)

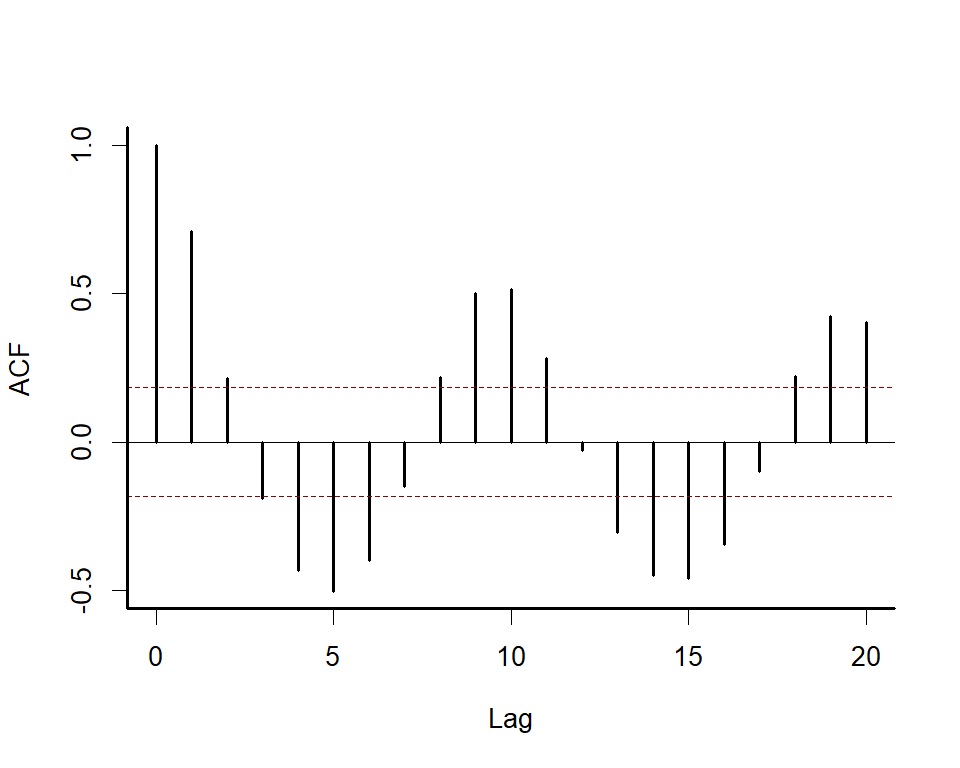

These plots show that the time series are count responses, with

missing data, many zeroes, seasonality and temporal autocorrelation all

present. These features make time series analysis and forecasting very

difficult using conventional software. But mvgam shines in

these tasks.

For most forecasting exercises, we’ll want to split the data into training and testing folds:

data_train <- portal_data %>%

dplyr::filter(time <= 60)

data_test <- portal_data %>%

dplyr::filter(time > 60 &

time <= 65)Formulate an mvgam model; this model fits a State-Space

GAM in which each species has its own intercept, linear association with

ndvi_ma12 and potentially nonlinear association with

mintemp. These effects are estimated jointly with a full

time series model for the temporal dynamics (in this case a Vector

Autoregressive process). We assume the outcome follows a Poisson

distribution and will condition the model in Stan using

MCMC sampling with Cmdstan:

mod <- mvgam(

# Observation model is empty as we don't have any

# covariates that impact observation error

formula = captures ~ 0,

# Process model contains varying intercepts,

# varying slopes of ndvi_ma12 and varying smooths

# of mintemp for each series.

# Temporal dynamics are modelled with a Vector

# Autoregression (VAR(1))

trend_formula = ~

trend +

s(trend, bs = 're', by = ndvi_ma12) +

s(mintemp, bs = 'bs', by = trend) - 1,

trend_model = VAR(cor = TRUE),

# Obvservations are conditionally Poisson

family = poisson(),

# Condition on the training data

data = data_train,

backend = 'cmdstanr'

)Using print() returns a quick summary of the object:

mod

#> GAM observation formula:

#> captures ~ 1

#>

#> GAM process formula:

#> ~trend + s(trend, bs = "re", by = ndvi_ma12) + s(mintemp, bs = "bs",

#> by = trend) - 1

#>

#> Family:

#> poisson

#>

#> Link function:

#> log

#>

#> Trend model:

#> VAR(cor = TRUE)

#>

#>

#> N latent factors:

#> 4

#>

#> N series:

#> 4

#>

#> N timepoints:

#> 60

#>

#> Status:

#> Fitted using Stan

#> 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1500; thin = 1

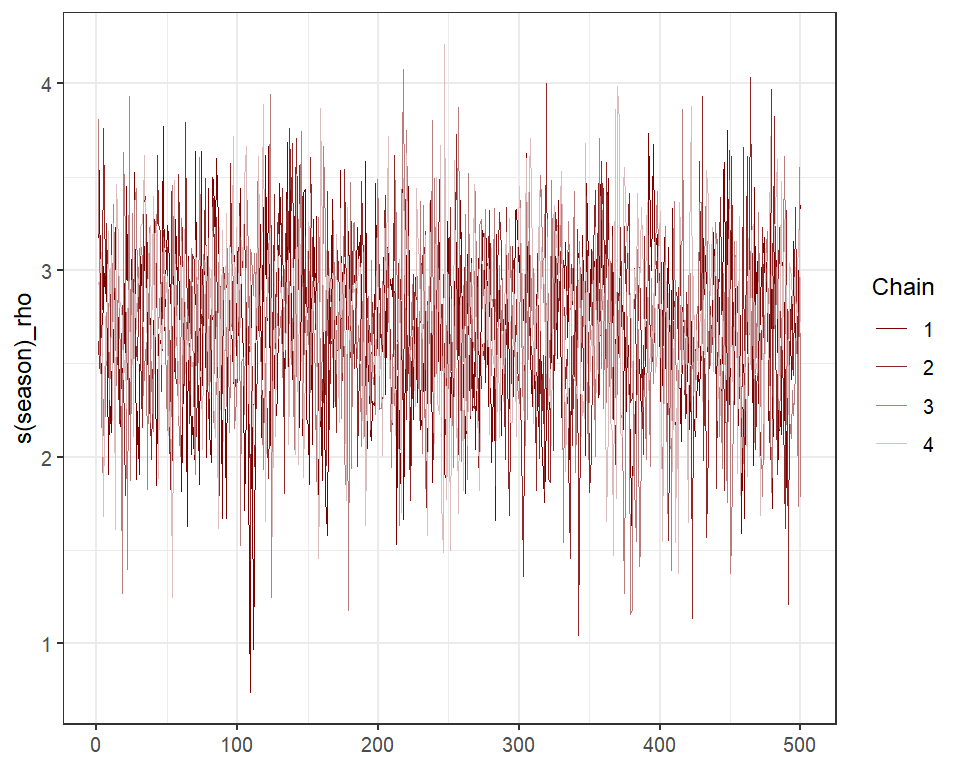

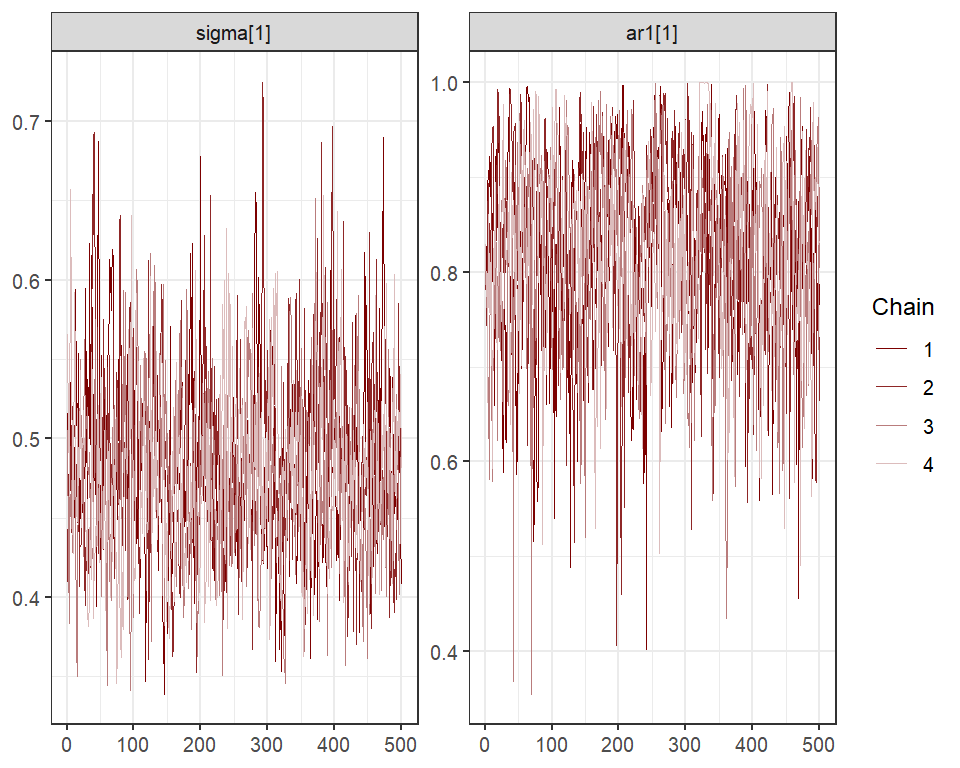

#> Total post-warmup draws = 2000Split Rhat and Effective Sample Size diagnostics show good convergence of model estimates

mcmc_plot(mod,

type = 'rhat_hist')

#> `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value `binwidth`.

mcmc_plot(mod,

type = 'neff_hist')

#> `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value `binwidth`.

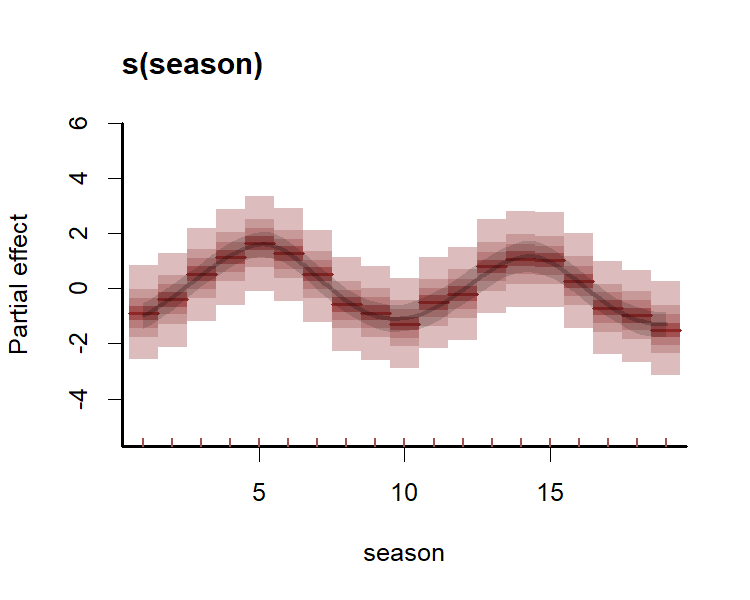

Use conditional_effects() for a quick visualisation of

the main terms in model formulae

conditional_effects(mod,

type = 'link')

If you have the gratia package installed, it can also be

used to plot partial effects of smooths

require(gratia)

draw(mod,

trend_effects = TRUE)

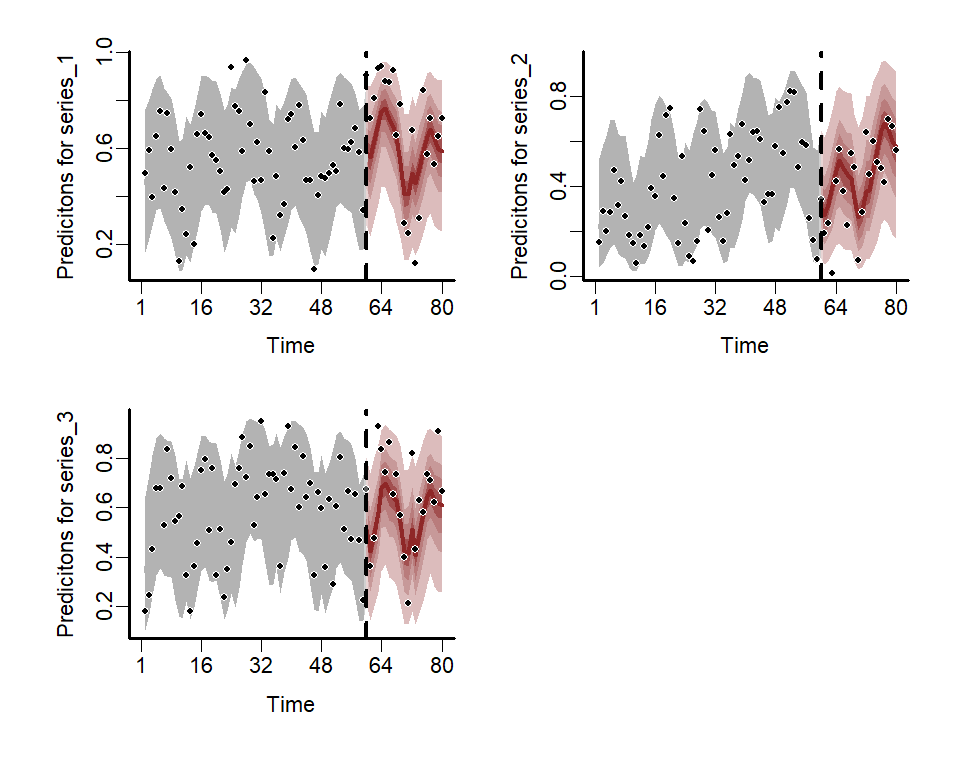

Or design more targeted plots using plot_predictions()

from the marginaleffects package

plot_predictions(

mod,

condition = c('ndvi_ma12',

'series',

'series'),

type = 'link'

)

plot_predictions(

mod,

condition = c('mintemp',

'series',

'series'),

type = 'link'

)

We can also view the model’s posterior predictions for the entire

series (testing and training). Forecasts can be scored using a range of

proper scoring rules. See ?score.mvgam_forecast for more

details

fcs <- forecast(mod,

newdata = data_test)

plot(fcs, series = 1) +

plot(fcs, series = 2) +

plot(fcs, series = 3) +

plot(fcs, series = 4)

#> Out of sample DRPS:

#> 8.23058125

#> Out of sample DRPS:

#> 5.33980075

#> Out of sample DRPS:

#> 8.71284175

#> Out of sample DRPS:

#> 3.83530975

For Vector Autoregressions fit in mvgam, we can inspect

impulse response functions and forecast error variance

decompositions. The irf() function runs an Impulse

Response Function (IRF) simulation whereby a positive “shock” is

generated for a target process at time t = 0. All else

remaining stable, it then monitors how each of the remaining processes

in the latent VAR would be expected to respond over the forecast horizon

h. The function computes impulse responses for all

processes in the object and returns them in an array that can be plotted

using the S3 plot() function. Here we will use the

generalized IRF, which makes no assumptions about the order in which the

series appear in the VAR process, and inspect how each process is

expected to respond to a sudden, positive pulse from the other processes

over a horizon of 12 timepoints.

irfs <- irf(mod,

h = 12,

orthogonal = FALSE)

plot(irfs,

series = 1)

plot(irfs,

series = 3)

Using the same logic as above, we can inspect forecast error variance

decompositions (FEVDs) for each process usingfevd(). This

type of analysis asks how orthogonal shocks to all process in the system

contribute to the variance of forecast uncertainty for a focal process

over increasing horizons. In other words, the proportion of the forecast

variance of each latent time series can be attributed to the effects of

the other series in the VAR process. FEVDs are useful because some

shocks may not be expected to cause variations in the short-term but may

cause longer-term fluctuations

fevds <- fevd(mod,

h = 12)

plot(fevds)

This plot shows that the variance of forecast uncertainty for each process is initially dominated by contributions from that same process (i.e. self-dependent effects) but that effects from other processes become more important over increasing forecast horizons. Given what we saw from the IRF plots above, these long-term contributions from interactions among the processes makes sense.

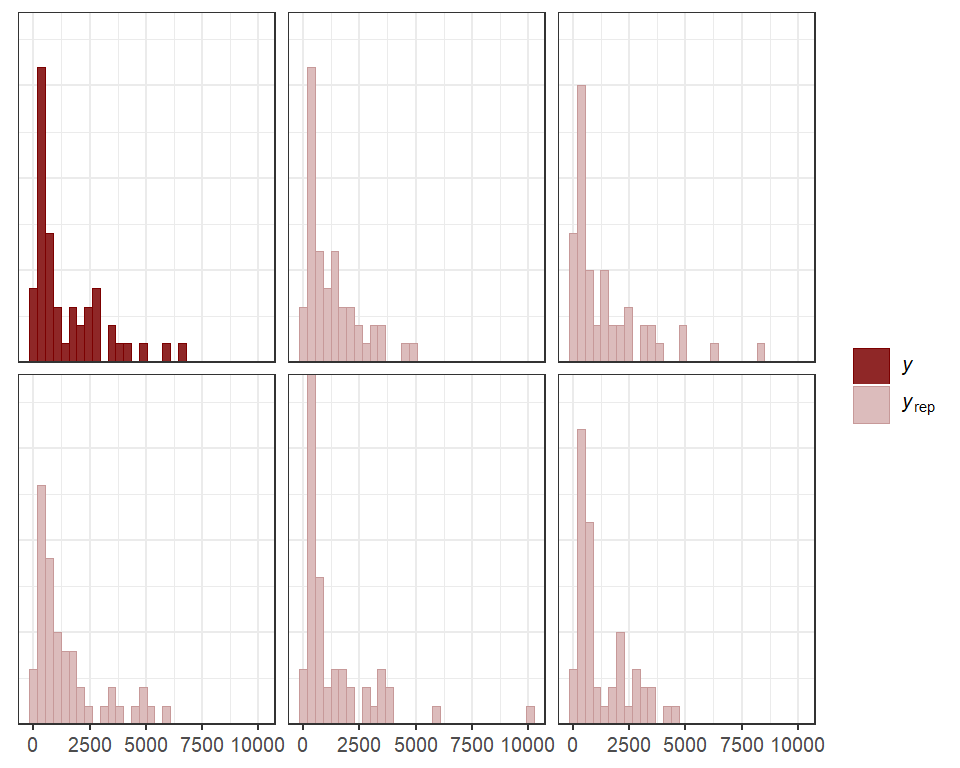

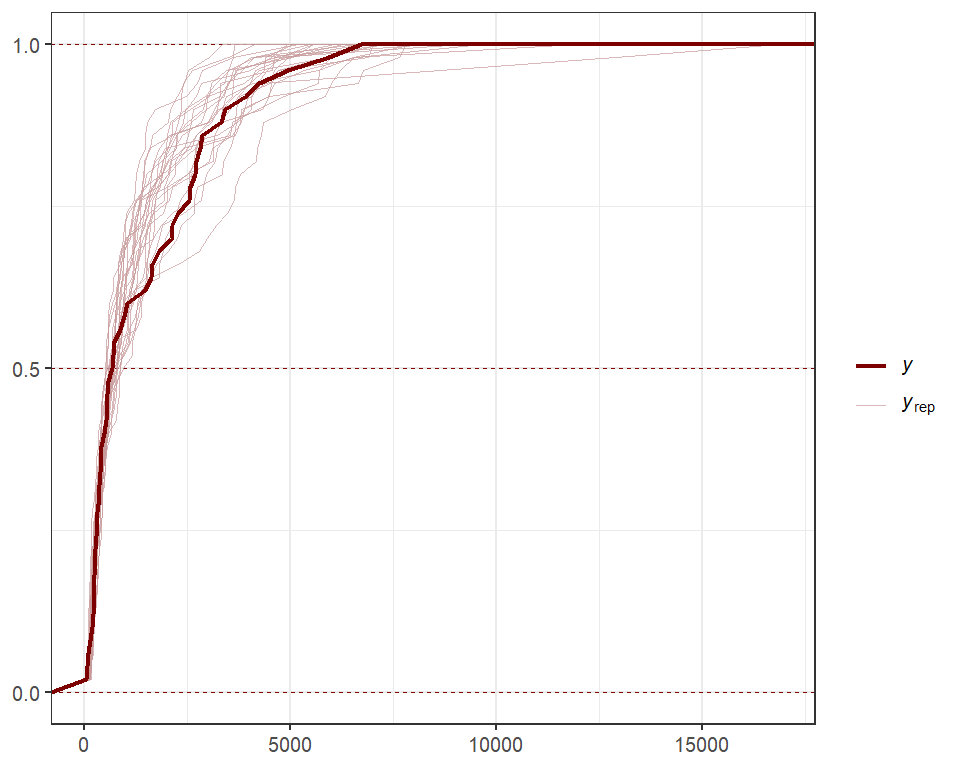

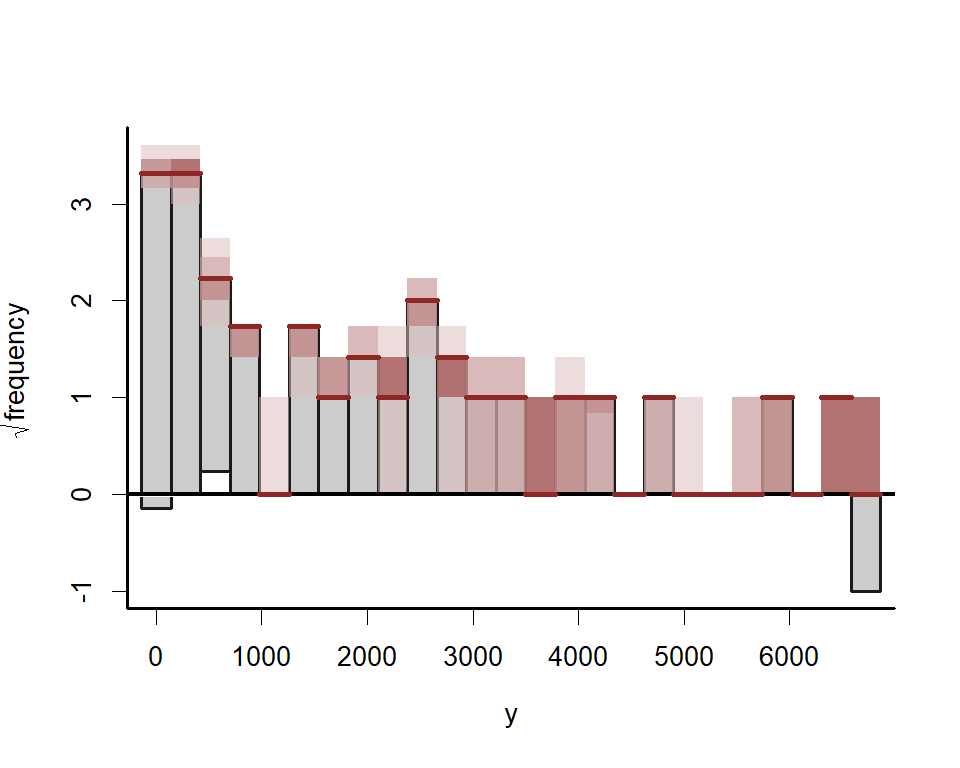

Plotting randomized quantile residuals over time for

each series can give useful information about what might be missing from

the model. We can use the highly versatile pp_check()

function to plot these:

pp_check(

mod,

type = 'resid_ribbon_grouped',

group = 'series',

x = 'time',

ndraws = 200

)

When describing the model, it can be helpful to use the

how_to_cite() function to generate a scaffold for

describing the model and sampling details in scientific

communications

description <- how_to_cite(mod)

description

#> Methods text skeleton

#> We used the R package mvgam (version 1.1.594; Clark & Wells, 2023) to

#> construct, fit and interrogate the model. mvgam fits Bayesian

#> State-Space models that can include flexible predictor effects in both

#> the process and observation components by incorporating functionalities

#> from the brms (Burkner 2017), mgcv (Wood 2017) and splines2 (Wang & Yan,

#> 2023) packages. To encourage stability and prevent forecast variance

#> from increasing indefinitely, we enforced stationarity of the Vector

#> Autoregressive process following methods described by Heaps (2023) and

#> Clark et al. (2025). The mvgam-constructed model and observed data were

#> passed to the probabilistic programming environment Stan (version

#> 2.38.0; Carpenter et al. 2017, Stan Development Team 2026), specifically

#> through the cmdstanr interface (Gabry & Cesnovar, 2021). We ran 4

#> Hamiltonian Monte Carlo chains for 1500 warmup iterations and 500

#> sampling iterations for joint posterior estimation. Rank normalized

#> split Rhat (Vehtari et al. 2021) and effective sample sizes were used to

#> monitor convergence.

#>

#> Primary references

#> Clark, NJ and Wells K (2023). Dynamic Generalized Additive Models

#> (DGAMs) for forecasting discrete ecological time series. Methods in

#> Ecology and Evolution, 14, 771-784. doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13974

#> Burkner, PC (2017). brms: An R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models

#> Using Stan. Journal of Statistical Software, 80(1), 1-28.

#> doi:10.18637/jss.v080.i01

#> Wood, SN (2017). Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R

#> (2nd edition). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

#> Wang W and Yan J (2021). Shape-Restricted Regression Splines with R

#> Package splines2. Journal of Data Science, 19(3), 498-517.

#> doi:10.6339/21-JDS1020 https://doi.org/10.6339/21-JDS1020.

#> Heaps, SE (2023). Enforcing stationarity through the prior in vector

#> autoregressions. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 32,

#> 74-83.

#> Clark NJ, Ernest SKM, Senyondo H, Simonis J, White EP, Yenni GM,

#> Karunarathna KANK (2025). Beyond single-species models: leveraging

#> multispecies forecasts to navigate the dynamics of ecological

#> predictability. PeerJ 13:e18929.

#> Carpenter B, Gelman A, Hoffman MD, Lee D, Goodrich B, Betancourt M,

#> Brubaker M, Guo J, Li P and Riddell A (2017). Stan: A probabilistic

#> programming language. Journal of Statistical Software 76.

#> Gabry J, Cesnovar R, Johnson A, and Bronder S (2026). cmdstanr: R

#> Interface to 'CmdStan'. https://mc-stan.org/cmdstanr/,

#> https://discourse.mc-stan.org.

#> Vehtari A, Gelman A, Simpson D, Carpenter B, and Burkner P (2021).

#> Rank-normalization, folding, and localization: An improved Rhat for

#> assessing convergence of MCMC (with discussion). Bayesian Analysis 16(2)

#> 667-718. https://doi.org/10.1214/20-BA1221.

#>

#> Other useful references

#> Arel-Bundock V, Greifer N, and Heiss A (2024). How to interpret

#> statistical models using marginaleffects for R and Python. Journal of

#> Statistical Software, 111(9), 1-32.

#> https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v111.i09

#> Gabry J, Simpson D, Vehtari A, Betancourt M, and Gelman A (2019).

#> Visualization in Bayesian workflow. Journal of the Royal Statatistical

#> Society A, 182, 389-402. doi:10.1111/rssa.12378.

#> Vehtari A, Gelman A, and Gabry J (2017). Practical Bayesian model

#> evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Statistics and

#> Computing, 27, 1413-1432. doi:10.1007/s11222-016-9696-4.

#> Burkner PC, Gabry J, and Vehtari A. (2020). Approximate leave-future-out

#> cross-validation for Bayesian time series models. Journal of Statistical

#> Computation and Simulation, 90(14), 2499-2523.

#> https://doi.org/10.1080/00949655.2020.1783262The post-processing methods we have shown above are just the tip of

the iceberg. For a full list of methods to apply on fitted model

objects, type methods(class = "mvgam").

mvgam was originally designed to analyse and forecast

non-negative integer-valued data. But further development of

mvgam has resulted in support for a growing number of

observation families. Currently, the package can handle data for the

following:

gaussian() for real-valued datastudent_t() for heavy-tailed real-valued datalognormal() for non-negative real-valued dataGamma() for non-negative real-valued databetar() for proportional data on

(0,1)bernoulli() for binary datapoisson() for count datanb() for overdispersed count databinomial() for count data with known number of

trialsbeta_binomial() for overdispersed count data with known

number of trialsnmix() for count data with imperfect detection (unknown

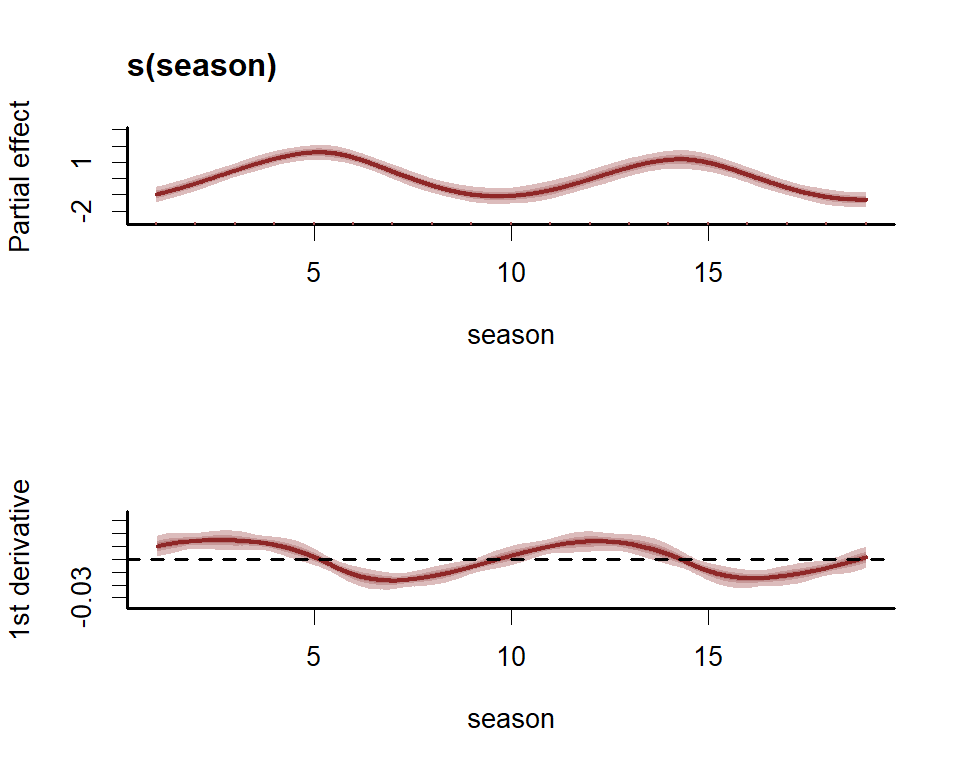

number of trials)See ??mvgam_families for more information. Below is a

simple example for simulating and modelling proportional data with

Beta observations over a set of seasonal series with

independent Gaussian Process dynamic trends:

set.seed(100)

data <- sim_mvgam(

family = betar(),

T = 80,

trend_model = GP(),

prop_trend = 0.5,

seasonality = "shared"

)

plot_mvgam_series(

data = data$data_train,

series = "all"

)

mod <- mvgam(

y ~ s(season, bs = "cc", k = 7) +

s(season, by = series, m = 1, k = 5),

trend_model = GP(),

data = data$data_train,

newdata = data$data_test,

family = betar()

)Inspect the summary to see that the posterior now also contains

estimates for the Beta precision parameters ϕ.

summary(mod,

include_betas = FALSE)

#> GAM formula:

#> y ~ s(season, bs = "cc", k = 7) + s(season, by = series, m = 1,

#> k = 5)

#>

#> Family:

#> beta

#>

#> Link function:

#> logit

#>

#> Trend model:

#> GP()

#>

#> N series:

#> 3

#>

#> N timepoints:

#> 80

#>

#> Status:

#> Fitted using Stan

#> 4 chains, each with iter = 1000; warmup = 500; thin = 1

#> Total post-warmup draws = 2000

#>

#> Observation precision parameter estimates:

#> 2.5% 50% 97.5% Rhat n_eff

#> phi[1] 7.8 12.0 18.0 1 1829

#> phi[2] 5.6 8.6 13.0 1 1023

#> phi[3] 4.1 6.0 8.7 1 1404

#>

#> GAM coefficient (beta) estimates:

#> 2.5% 50% 97.5% Rhat n_eff

#> (Intercept) 0.11 0.45 0.7 1.01 602

#>

#> Approximate significance of GAM smooths:

#> edf Ref.df Chi.sq p-value

#> s(season) 3.9071 5 9.792 0.0653 .

#> s(season):seriesseries_1 1.0934 4 11.307 0.2695

#> s(season):seriesseries_2 2.5629 4 2.227 0.4544

#> s(season):seriesseries_3 0.8565 4 6.556 0.5358

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> marginal deviation:

#> 2.5% 50% 97.5% Rhat n_eff

#> alpha_gp[1] 0.150 0.40 0.88 1.00 828

#> alpha_gp[2] 0.570 0.93 1.50 1.00 1018

#> alpha_gp[3] 0.052 0.40 0.92 1.01 672

#>

#> length scale:

#> 2.5% 50% 97.5% Rhat n_eff

#> rho_gp[1] 1.2 3.6 11 1.00 1482

#> rho_gp[2] 3.0 12.0 30 1.01 367

#> rho_gp[3] 1.3 4.9 26 1.00 532

#>

#> Stan MCMC diagnostics:

#> ✔ No issues with effective samples per iteration

#> ✔ Rhat looks good for all parameters

#> ✔ No issues with divergences

#> ✔ No issues with maximum tree depth

#>

#> Samples were drawn using sampling(hmc). For each parameter, n_eff is a

#> crude measure of effective sample size, and Rhat is the potential scale

#> reduction factor on split MCMC chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1)

#>

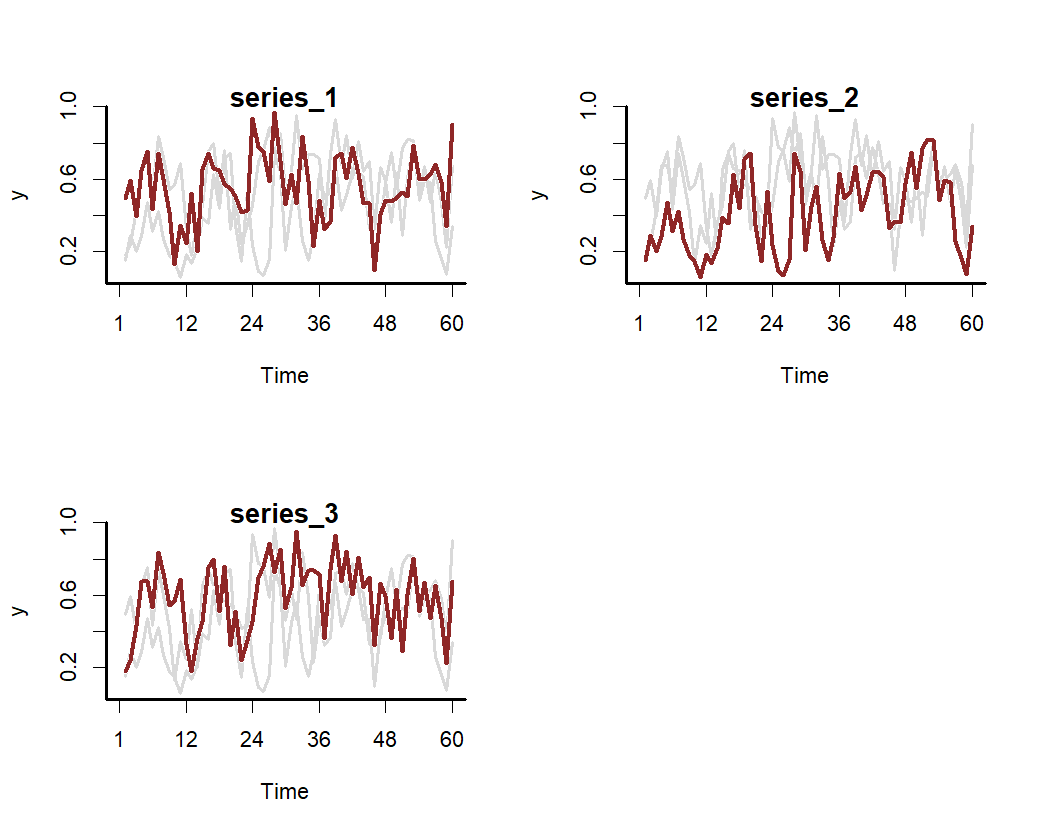

#> Use how_to_cite() to get started describing this modelPlot the hindcast and forecast distributions for each series

library(patchwork)

fc <- forecast(mod)

wrap_plots(

plot(fc, series = 1),

plot(fc, series = 2),

plot(fc, series = 3),

ncol = 2

)

There are many more extended uses of mvgam, including

the ability to fit hierarchical State-Space GAMs that include dynamic

and spatially varying coefficient models, dynamic factors, Joint Species

Distribution Models and much more. See the

package documentation for more details.

mvgam can also be used to generate all necessary data

structures and modelling code necessary to fit DGAMs using

Stan. This can be helpful if users wish to make changes to

the model to better suit their own bespoke research / analysis goals.

The Stan Discourse is a helpful place to

troubleshoot.

mvgam and

related softwareWhen using any software please make sure to appropriately acknowledge the hard work that developers and maintainers put into making these packages available. Citations are currently the best way to formally acknowledge this work (but feel free to ⭐ this repo as well).

When using mvgam, please cite the following:

Clark, N.J. and Wells, K. (2023). Dynamic Generalized Additive Models (DGAMs) for forecasting discrete ecological time series. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13974

As mvgam acts as an interface to Stan,

please additionally cite:

Carpenter B., Gelman A., Hoffman M. D., Lee D., Goodrich B., Betancourt M., Brubaker M., Guo J., Li P., and Riddell A. (2017). Stan: A probabilistic programming language. Journal of Statistical Software. 76(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v076.i01

mvgam relies on several other R packages

and, of course, on R itself. Use how_to_cite()

to simplify the process of finding appropriate citations for your

software setup.

If you encounter a clear bug, please file an issue with a minimal

reproducible example on GitHub. Please

also feel free to use the mvgam

Discussion Board to hunt for or post other discussion topics related

to the package, and do check out the mvgam

Changelog for any updates about recent upgrades that the package has

incorporated.

A series of vignettes cover data formatting, forecasting and several extended case studies of DGAMs. A number of other examples, including some step-by-step introductory webinars, have also been compiled:

mvgam

packagemgcv and mvgammvgamI’m actively seeking PhD students and other researchers to work in

the areas of ecological forecasting, multivariate model evaluation and

development of mvgam. Please reach out if you are

interested (n.clark’at’uq.edu.au). Other contributions are also very

welcome, but please see The

Contributor Instructions for general guidelines. Note that by

participating in this project you agree to abide by the terms of its Contributor Code of

Conduct.

The mvgam project is licensed under an MIT

open source license